evaluation-guidebook

/

app

/src

/content

/chapters

/general-knowledge

/model-inference-and-evaluation.mdx

| --- | |

| title: "Model inference and evaluation" | |

| --- | |

| import llmTk1 from '../../assets/image/llm_tk_1.png'; | |

| import llmLogprob from '../../assets/image/llm_logprob.png'; | |

| import llmGen from '../../assets/image/llm_gen.png'; | |

| import Image from '../../../components/Image.astro'; | |

| import Note from "../../../components/Note.astro"; | |

| import Sidenote from "../../../components/Sidenote.astro"; | |

| import Accordion from "../../../components/Accordion.astro"; | |

| Current large language model work in a simple way: given some text as input, they have learned to predict plausible follow up. | |

| This is done in two steps. | |

| ### Tokenization | |

| The input text (called a *prompt* at inference) is first split into *tokens*, small units of texts (which can be one or several characters, up to the word level) each associated with a number. The whole range of tokens a model can parse is called its *vocabulary*. This section is quite basic so feel free to skip it if needed! | |

| #### Basics of tokenization: Why and how do we tokenize text? | |

| Since large language models are actually big mathematical functions, they eat numbers, not text. | |

| Say you want to transform a sentence to numbers. You first need to decide how to cut your sentence into small pieces, then map every small piece to a number; this is *tokenization*. | |

| In the past, people would try to map each character of a text with its index in a alphabet (`a` -> 1, `b` -> 2, etc) which is called *character based tokenization* (you split between characters). On the other end of the spectrum, people also tried to map each word with its index in a dictionary (`a` -> 1, `aardvark` -> 2, `ab` -> 3, etc) which is called *word based tokenization* (you split on spaces, if your language has spaces - if not, it's a bit harder). | |

| Both these methods share a strong limitation: they remove information from the input text. They erase semantic connections that you can see from word shape (ex: `dis similar`, `similar`, `similar ity`, `similar ly`), information we would like our model to retain, so it connects related words together. | |

| (Plus, what happens if you suddenly have a completely new word in input? It gets no number, and your model can't process it 😔 ) | |

| Some people therefore had the idea to cut words into sub-words, and assign index to these sub-words (`dis`, `similar`, `ity`, `ly`)! | |

| This was initially done using morpho-syntactic rules (*morpho-syntax* is like the grammar of word creation). Now most people use byte pair encoding (BPE), a smart statistical method to create the sub-words automatically depending on their frequency in a reference text. | |

| So as a summary: tokenization is a way to map small units of texts (which can be one or several characters, up to the word level) to numbers (similar to an index). When you want to process text, your input text (called a *prompt* at inference) is split into these *tokens* by a tokenizer. The whole range of tokens a model or tokenizer can parse is called its *vocabulary*. | |

| <Note title="Going further: Understanding tokenization" emoji="📚" variant="warning"> | |

| - ⭐ [Explanation of different tokenization methods in the 🤗 NLP Course](https://huggingface.co/learn/nlp-course/en/chapter2/4) | |

| - ⭐ [Conceptual guide about tokenization in the 🤗 doc](https://huggingface.co/docs/transformers/en/tokenizer_summary) | |

| - [Course by Jurafsky on tokenization (and other things)](https://web.stanford.edu/~jurafsky/slp3/2.pdf) - academic approach, skip to 2.5 and 2.6 (the rest is interesting too but too broad) | |

| </Note> | |

| <Note title="Going further: Byte Pair Encoding" emoji="📚" variant="warning"> | |

| - ⭐ [Explanation of BPE in the 🤗 NLP Course](https://huggingface.co/learn/nlp-course/en/chapter6/5) | |

| - [Paper introducing BPE to NLP](https://aclanthology.org/P16-1162/) | |

| </Note> | |

| #### Using your own tokenizer? Don't forget to consider the following | |

| I recommend making sure you understand BPE before this section, see above for some references! | |

| **Choosing the correct vocabulary size** | |

| The size of the vocabulary indicates how many individual tokens (for example, sub-words) the model will have to learn. A vocabulary which is **too big** might contain some very rare words as full tokens (for example: `aardvark`), which can lead to 2 problems. If such a rare word almost never appears in the training data, it can be hard to connect to other concepts, and the model might be unable to infer what it is about. On the other hand, if it appears rarely and only in specific contexts, it can be linked to some very specific other words: for example, if you train on forum data, and your tokenizer mapped a username as one single token in its vocabulary, your model might then associate this token to the specific user's content. | |

| A vocabulary which is **too small** will present 2 other problems: worst representation capabilities, and increased cost at inference. | |

| Let's go back to our above example, where we tokenized words derived from `similar`. Using a pseudo BPE approach (large vocabulary) to tokenize `similarly` has split the word into 2 tokens (`similar`, `ly`). If we had used instead character level tokenization (therefore with a very small vocabulary, the size of an alphabet), the same word would be cut into 9 tokens (`s`, `i`, `m`, `i`, `l`, `a`, `r`, `l`, `y`). Where the first method splits `similarly` into tokens which have an individual semantic meaning, it's not the case in the second method: with too small a vocabulary, we lost some semantic representation. The difference in representations length also means that it's many times as costly to generate our word with a smaller vocabulary (takes 9 tokens instead of 2, so 5 times more costly!). | |

| At the moment, most people seem to use heuristics for vocabulary size, which seems correlated to number of languages covered and model size, so it's likely that using a number of tokens close to the reference models of a similar size could work for you. | |

| <Note title="Going further: Rare tokens effect" emoji="📚"> | |

| - [SolidGoldMagikarp post on Less Wrong](https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/aPeJE8bSo6rAFoLqg/solidgoldmagikarp-plus-prompt-generation): Very interesting read on how some people identified very rare tokens in Open AI's vocabulary - this is quite cool because it's done without access to the model's internals (we don't know what the training data contains for example) | |

| - [Fishing for Magikarp, paper by Cohere](https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.05417): Follow up work on to detect these tokens | |

| </Note> | |

| **Managing several languages** | |

| When building or choosing your tokenizer, you construct your vocabulary from reference text. This means that your tokenizer will know vocabulary words and characters from this reference text. Usually, it means using data in English, with a Latin script. | |

| If you want to add new language, and your new language uses the same script and share some roots, you could theoretically hope that some of your original language semantics transfer to the new language. | |

| However, if you want to allow your tokenizer to correctly split text in other languages (especially languages written in other scripts) you'd better include data from these languages when building said tokenizer. Most of the time, though, this data will contain an unbalanced proportion of the initial language (ex: English) to the new language (ex: Thai, or Burmese), the initial language being much more present. Since most efficient tokenizer methods used nowadays (like BPE) create their complex vocabulary tokens based on the most frequent words seen, most of the long tokens will be English words - and most of the words from the less frequent languages will only be split at the character level. | |

| This effect leads to an unfairness in multilingual tokenization: some (less frequent, or *lower-resourced*) languages require orders of magnitude more tokens to generate a sentence of equivalent length as English. | |

| <iframe | |

| src="https://OpenEvals-tokenizers-languages.hf.space" | |

| frameborder="0" | |

| width="850" | |

| height="450" | |

| ></iframe> | |

| <Note title="Going further: Language and tokenization" emoji="📚" variant="warning"> | |

| - ⭐ [A beautiful breakdown and demo by Yennie Jun on tokenization issues across languages](https://www.artfish.ai/p/all-languages-are-not-created-tokenized): The breakdown in itself is very clear, and the embedded space comes from her work. | |

| - ⭐ [A demo by Aleksandar Petrov on unfairness of tokenization](https://aleksandarpetrov.github.io/tokenization-fairness/): I recommend looking at `Compare tokenization of sentences` to get a feel for the differences in cost of inference depending on languages | |

| </Note> | |

| **What about numbers?** | |

| When building your tokenizer, you need to decide what to do about numbers. Do you only index 0 to 9, and assume all other numbers will be compositions of digits, or do you want to store numbers up to, say, one billion, individually? Current well known models display a range of approaches to this, but it's unclear what works better to allow mathematical reasoning. Maybe new approaches to tokenization, such as hierarchical tokenization, might be needed for this. | |

| <Note title="Going further: Number tokenization" emoji="📚" variant="warning"> | |

| - ⭐ [A nice visual demo by Yennie Jun of how tokenizers of Anthropic, Meta, OpenAI, and Mistral models split numbers](https://www.artfish.ai/p/how-would-you-tokenize-or-break-down) | |

| - [Small history by Beren Millidge of the evolution of number tokenization through the years](https://www.beren.io/2024-05-11-Integer-tokenization-is-now-much-less-insane/) | |

| </Note> | |

| #### How tokenization can mess up your evaluation | |

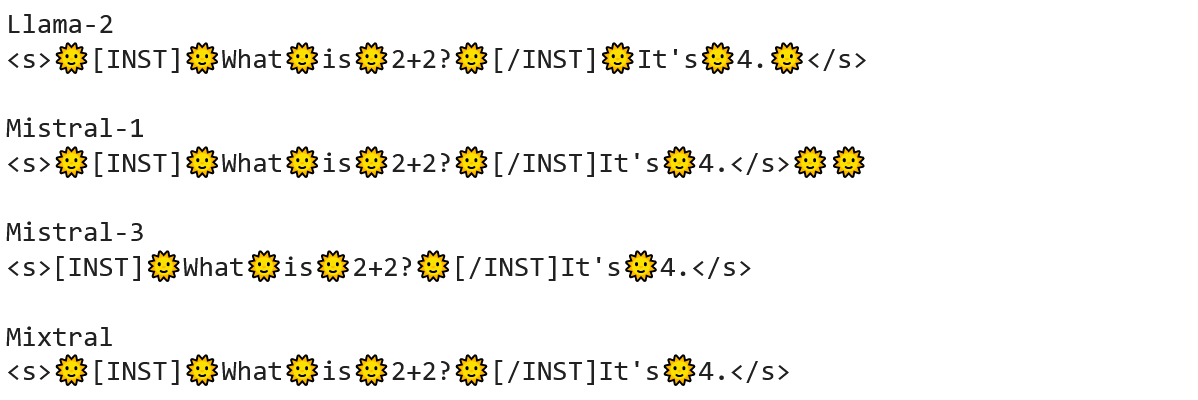

| **Managing fine-tuned models, system prompts and chat templates** | |

| Pre-2022, models used to simply be pretrained: text in, text out, nothing else. Then, we got instruction tuning and chat models in 2023, and in 2025 reasoning models. This means that we went from using text "as is" to using chat templates (= providing models with json) to using reasoning tags (= mixing up the json chat template with xml tags for reasoning). | |

| This means a number of models are going to perform terribly if you do not make sure to: | |

| 1. add their system prompt at the very beginning of inference | |

| 2. prompt them using a chat template if they require it (usually adding `Assistant` and `User` prefixes to the dialogue turns - learn more about this in [this cool guide](https://huggingface.co/docs/transformers/main/en/chat_templating)) | |

| 3. remove the thinking trace from the model answer before processing it (you can usually regex to remove what's between the `<think>` tags) | |

| <Note title="Critical: Chat templates and tokenization" emoji="⚡" variant="danger"> | |

|  | |

| Different tokenizers behave differently with spacing and special tokens. See this [visualization](https://x.com/danielhanchen/status/1796952220619157694) showing how spacing, tokenization, and templates interact. Never assume tokenizers behave identically! | |

| </Note> | |

| **Tokenizing the context and choices together or separately** | |

| When looking at an MCQA evaluation, in general, you want to tokenize the context together with the choices, as it creates a succession of tokens which is likely/natural for the model. | |

| <Note title="Should you tokenize the context with the choices always?"> | |

| Some tokenizers (like the [Llama one](https://github.com/EleutherAI/lm-evaluation-harness/pull/531#issuecomment-1595586257)) do not satisfy `enc(context + choice) = enc(context) + enc(choice)` (and add or remove spacing). This means that comparing the logprobabilities of the choices only is not trivial, as the context tokens can "bleed out" into them, messing up the comparison. | |

| To give a concrete example, say you have characters `C1`, `C2`, and `C3` as base tokens of your vocabulary, and `C1C2` also happens to be a single token learned during BPE. | |

| Say your context is C1, and the choices C2 and C3. | |

| If you tokenize the context with the choices, you compare `C1C2` (one token) with `C1+C3` (two tokens). Even if you normalize the logprobs by length, you are not comparing the same thing. | |

| Comparing after tokenizing the context and choices separately means you compare `C1+C2` and `C1+C3`. But since `C1C2` is a token, the occurence of `C1+C2` is likely rare in the data your encoder saw, so it is an unlikely succession for your model, which can mess up your logprobabilities. | |

| If this is the case for your model, the solution is usually to go for the least worst option, comparing the comparable: compute the tokens of context and choice separately and then concatenate them after removing the special start/end of sentence tokens which might have been added. | |

| </Note> | |

| **Paying attention to start and end of sentence tokens** | |

| Some pretrained models, like the `Gemma` ones, are extremely sensitive to the [inclusion of start of sentence tokens](https://github.com/EleutherAI/lm-evaluation-harness/pull/1465) at inference. You might need to do a couple of experiments to see if that happens for you, and add these tokens manually when evaluating. | |

| You can also encounter some issues where your model won't stop on an end of sentence token like you would expect (for example, on `\n`), because your model will not predict this token alone but included in an higher level token (for example, `\n\n`, which can be a single token, especially for code models). In this case, you might need to add a specific check to "backtrack" on generated text to make sure you're cutting your generated sentence at the proper spot before computing metrics. | |

| **Multilinguality and tokenization** | |

| When looking at multilingual evaluations, you'll also need to see how to tokenize your text, depending on your evaluation task and metrics. As some languages do not always use spacing as a word separator (Korean, Thai, Japanese, Chinese, to cite a few), they will require language specific tokenizers to be split properly, else it will affect their scores on metrics such as [BLEU](https://github.com/EleutherAI/lm-evaluation-harness/issues/212), F1 scores, etc. The number of tokens that the model is allowed to generate for an evaluation should also be language dependent, as not all languages are tokenized in similar amount of tokens (go back to the tokenization section to see why). | |

| **Code evaluations and end of sentence tokens** | |

| Code models usually have been trained with `\n\t` as a single token. This means that when generating text, they will often generate `\n\t` in one step. A task which defines `\n` as an end of sentence token (= to stop the generation) will let the model continue generating after a `\n\t`, if predicted as one token, since it's not the same as `\n`. But you would actually still want the model to stop. In these cases, you either need to update your end of sentence tokens, or define a mechanism to backtrack on the character representation of the latest tokens to stop (and cut) the generation a posteriori. | |

| ### Inference | |

| From this input text, the LLM generates a probability distribution of the most likely next tokens over all the vocabulary. To get a continued generation, we can take the most probable token (give or take some added randomness to get more interesting outputs) as the next one, then repeat the operation, using the new token as the end of the prompt, etc. | |

| <Image src={llmTk1} alt="LLM tokenization and prediction process" /> | |

| <Note title="Two main evaluation approaches" emoji="🎯" variant="info"> | |

| **Log-likelihood evaluations**: Given a prompt and one (or several) answers, what is probability of said answer(s) for my model? | |

| **Generative evaluations**: Given a prompt, what text does my model generate? | |

| Choice depends on your task: multiple-choice questions use log-likelihood, while open-ended tasks require generative evaluation. | |

| </Note> | |

| #### Log-likelihood evaluations | |

| For log-likelihood evaluations, we want the conditional probability of one or several choices given a prompt - in other terms, what is the likelihood to get a specific continuation given an input? | |

| So: | |

| - we concatenate each choice with the prompt, and pass them to our LLM, which outputs the logits of each token depending on the previous ones | |

| - we only keep the last logits (associated with the choice tokens), and apply a log softmax to get log-probabilities (where the range is `[-inf, 0]` instead of `[0-1]`) | |

| - we then sum all individual tokens log probabilities to get the overall choice log probability | |

| - we can finally apply a normalization based on choice length | |

| <Image src={llmLogprob} alt="LLM log-likelihood evaluation process" /> | |

| This allows us to apply one of the following metrics: | |

| - get the preferred answer of a model among several choice, like in the above picture. (*However, this can advantage scores of models which would have, freely, generated something else, like `Zygote` in the picture.*) | |

| - test if a single choice has a probability above 0.5 | |

| - study model calibration. A well calibrated model is a model for which the correct answers have the highest probabilities. | |

| <Sidenote> | |

| To learn more about calibration, you can check [this paper](https://arxiv.org/abs/2207.05221) from Anthropic, on what it is, how to detect it, and how to train models to be well calibrated, and [this paper](https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.14648) on some possible limits of calibration). | |

| </Sidenote> | |

| <Note> | |

| A multiple choice question answer can be expressed as a free form generative evaluation too! For this reason, you'll sometimes see a mention of the task **formulation**. | |

| There are three common task formulations: | |

| - **Multiple choice format (MCF)**: we compare the likelihood of choices indices, where choices are explicitly presented in the prompt and prefixed with A/B/C/D (as in MMLU) | |

| - **Cloze formulation (CF)**: we compare the likelihood of different choices without providing them in the prompt | |

| - **Freeform generation (FG)**: we evaluate the accuracy of greedy generation for a given prompt | |

| FG requires substantial latent knowledge and is usually too difficult for models during short pre-training ablations. For this reason, we typically focus on multiple choice formulations (MCF or CF) when running small-scale ablations. However, for post-trained models, FG becomes the primary formulation since we're evaluating whether the model can actually generate useful responses. | |

| However, research has also shown that models struggle with MCF early in training, only learning this skill after extensive training, making CF better for early signal. We thus recommend using CF for small ablations, and integrate MCF in the main run as it gives better mid-training signal once a model has passed a threshold to get sufficiently high signal-over-noise ratio for MCF. | |

| A quick note also that, to score a model's answer in sequence likelihood evaluations like CF, we compute accuracy as the percentage of questions where the the correct answer has the highest log probability normalised by character/token count. This normalisation prevents a bias toward shorter answers. | |

| <Sidenote> | |

| The point at which MMLU MCF becomes non-random depends on the model size and training data. For a 7B transformer, the OLMES paper found the model starts showing non-random performance after 500B tokens. For 1.7B model, we found this happens after 6T tokens in SmolLM2. | |

| </Sidenote> | |

| </Note> | |

| #### Generative evaluations | |

| For a generative evaluation, we want the text generated by the model given an input prompt. | |

| It is obtained in an auto-regressive way: we pass the prompt to the model, look at the most likely next token, select it as being the model's "choice first token", then repeat until we reach an end of generation condition (maximum length, special token to stop the generation, etc). All the tokens generated by the model are consider its answer to the prompt. | |

| <Image src={llmGen} alt="LLM generative evaluation process" /> | |

| We can then compare this generation with references and score the distance between both (using either simple metrics like exact match, more complex metrics like BLEU, or models as judges). | |

| <Note title="Going further" emoji="📚" variant="warning"> | |

| - ⭐ [Blog on several ways to evaluate MMLU](https://huggingface.co/blog/open-llm-leaderboard-mmlu) , by my team at Hugging Face. I recommend reading it if you want to delve deeper into the differences between multi choice log-likelihood evaluations and generative ones, including what it can mean with respect to score changes (The above illustrations come from the blog and have been made by Thom Wolf) | |

| - ⭐ [A beautiful mathematical formalization of the above inference methods](https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.14782v2), from EleutherAI. Go to the Appendix directly. | |

| </Note> | |

| ### Constraining model outputs | |

| In a number of cases, we want the model output to follow a specific format, for example to compare them to a reference. | |

| #### Using a prompt | |

| The easiest way to do this is to add a task prompt which contains very specific instructions as to how the model should answer (`Provide numerical answers in digits.`,`Use no abbreviation.`, etc). | |

| It won't necessarily work all the time but should be good enough for high capability models. That's the approach we followed in the [GAIA](https://huggingface.co/papers/2311.12983) paper for example. | |

| #### Few shots and in context learning | |

| The next way to do so is to constrain the model through what is called "in context learning". By providing examples in the prompt (what is called `few-shot prompting`), the model is implicitly biased towards following the repeated prompt shape for the actual sample. | |

| <Note> | |

| It's a method which was overall working quite well until end of 2023! | |

| However, the widespread adoption of instruction-tuning methods and the addition of instruction data in later stages of model pre-training (continuous pre-training) has biased more recent models towards specific output formats (what is being called [here](https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.07890) *Training on the test task*, and what I would call *overfitting the prompt format*). Reasoning models are also not playing that well with few shot examples because of the reasoning trace. | |

| It's also a method which can be limited for older models with smaller context sizes, as some few-shot examples can not fit into the context window. | |

| </Note> | |

| #### Structured text generation | |

| Structured text generation constrains the outputs to follow a given path, defined by a grammar or by regular expressions, for example. The `outlines` library implements this using finite state machines, which is very neat. (Other approaches exist, such as using interleaved generation for json generation, but the FSM one is my favorite). | |

| To understand more about what happens when using structured generation, you can check the [blog](https://huggingface.co/blog/evaluation-structured-outputs) we wrote together: structured generation reduce prompt variance in evaluation, and make results and rankings more stable. You can also check the overall `outlines` [blog](https://blog.dottxt.co/) for interesting implementations and observations linked to structured generation. | |

| However, some recent [research](https://arxiv.org/abs/2408.02442) seems to show that structured generation can lower model performance on some tasks (like reasoning), by moving the prior too far away from the expected probability distribution. | |

| <Note title="Going further" emoji="📚" variant="warning"> | |

| - ⭐ [Understanding how Finite State Machine when using structured generation](https://blog.dottxt.co/coalescence.html), by Outlines. Super clear guide on how their method works! | |

| - [The outlines method paper](https://arxiv.org/abs/2307.09702), a more academic explanation of the above | |

| - [Interleaved generation](https://github.com/guidance-ai/guidance?tab=readme-ov-file#guidance-acceleration), another method to constrain generations for some specific output formats | |

| </Note> |